An Invitation

Some years ago, I was conducting a workshop in the great state of North Carolina. Since I was going to be in Charlotte for a few days, I decided to visit a few schools to see what their math programs were like. At one school, I was asked to observe a 5th grader who shall go by the name of Lucas, who, I was told, disliked math intensely. Being open to the challenge of converting someone to my team, I eagerly jumped at the opportunity to observe Lucas and then spend some time with him afterwards.

I observed a perfectly anodyne lesson on fractions, and while it was far from inspiring, the teacher conducting it was perfectly civil to the children, and everyone seemed content and on task. That is, everyone except Lucas, who appeared fidgety and distracted during the lesson, and when it came time to practice the skill that was taught that day, spent a fair amount of time banging his head on the edge of the desk.

My chat with Lucas

At the end of the lesson, I was left alone to chat with Lucas. Having lived in Brooklyn all these years, I got right down to business. “Lucas, I understand you don’t like math, ” I said, “why is that?” In his best drawl, Lucas responded, “Teacher says I’m really bad at math….” “Oh,” I said, “why would she say that?” Lucas drew a breath and then stated, “Teacher says I don’t know my multiplication tables….”

I nodded my head, and replied, “Well, Lucas, that’s not uncommon for a fifth grader. Tell me, what’s 6 x 4?” Lucas’ eyes glazed over at this inquiry and in an almost robotic voice he answered, “six times four is twenty-four.” Okay, I thought, pretty good. Let’s see what else he knows. “How much is 7 x 7?” I asked. Again with the eye-glazing and the robot voice: “seven times seven is forty nine..”

The Full Picture

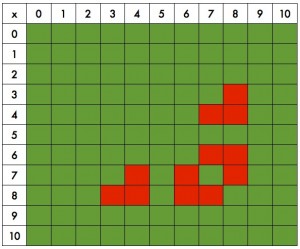

What eventually emerged was that Lucas knew all but about 6 multiplication facts, which included the usual “tough facts” like 6 x 8, 7 x 8 and 7 x 6. If we observe that there are only 66 individual multiplication facts (because multiplication is commutative, so once you learn 5 x 6, you also know 6 x 5), then it should be understood that Lucas knew 10/11 of these facts, which comes out to 91% proficiency. Of course, whenever Lucas encountered one of these facts, he most likely had to stop and either skip count or perform some other inefficient strategy, which left the teacher to conclude that he didn’t have command of this essential piece of knowledge.

At the conclusion of our brief time together, I said the following: “Lucas, it’s not that you don’t know your multiplication facts; it’s that you don’t know all of them yet.” Lucas gave me a quizzical look, then paused for a moment while he meditated on what I said. Then he shrugged his shoulders, we shook hands and walked out of the room together.

Teacher Recommendations

I spoke with Lucas’ teacher, Mrs. Peabody (not her actual name) and asked that she do two things. The first was that Lucas make a list of the 6 math facts that he didn’t know (yet) and commit to memorizing them during the next few weeks. I also asked that Lucas be able to keep a “cheat sheet” on his desk during that time so that he could look up any of those missing facts, with the understanding that he would remove them from the sheet when he had developed automaticity. I also asked her to have a sit-down with Lucas and discuss ways to help him overcome the frustration he felt in class: nobody wants a 10 year old to pound his head against the desk when doing math. He should wait until he’s an adult, when there are real problems to get upset about.